Jailhouse Lawyers:

Legal Empowerment and Civil Legal Problem-Solving

Project Partner: The Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative

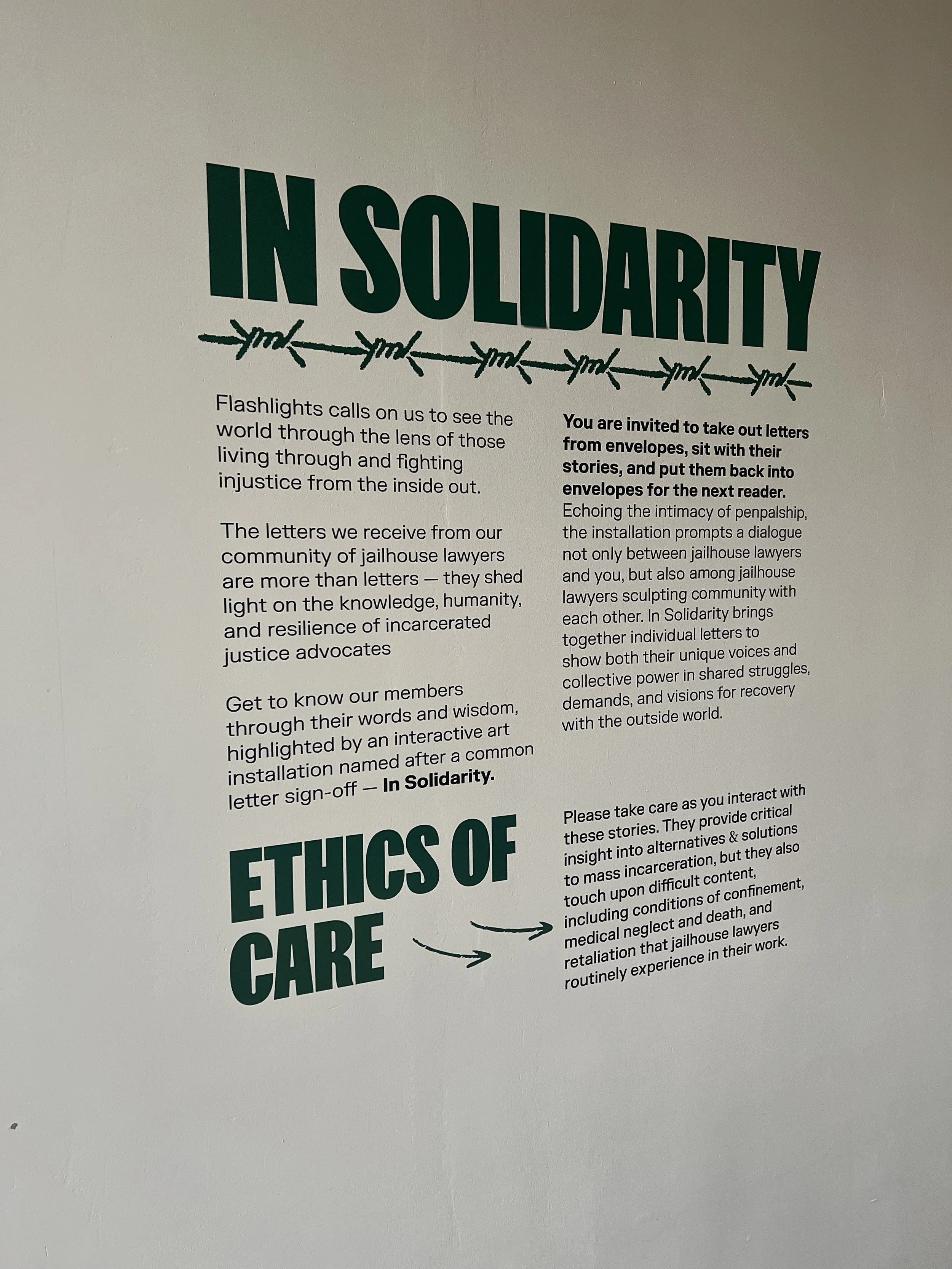

The Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative (JLI) was founded by Jhody Polk, a formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyer from Florida and 2018 Soros Justice fellow. JLI invests in jailhouse lawyers— incarcerated individuals who teach themselves the law to advocate for themselves and the rights of their peers. JLI uses a combination of legal education, movement building, participatory research, peace building, and advocacy to bring visibility to jailhouse lawyers and ensure they have the resources to know, use, and shape law through a legal empowerment framework: shifting power, knowledge, and resources to directly affected communities so they can activate systems, lead justice struggles, and become the authors of their own liberation.

Project Background

More than 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States and many of them represent themselves pro se and work with jailhouse lawyers for assistance. The United States Supreme Court in Johnson v. Avery and Bounds v. Smith held that incarcerated individuals have a constitutionally protected right to access the courts, which can include helping other incarcerated individuals with their legal issues, effectively creating a UPL carve out for jailhouse lawyers during incarceration. Jailhouse lawyers are already helping incarcerated community members with legal issues like family law matters, administrative grievances, parole/probation, habeas corpus petitions, and more through legal writing, research and analysis but are unable to continue that work after they are released.

Much of the existing access to justice conversations in the U.S. are focused squarely within the civil justice system, further exacerbating the existing problem-solving siloes that have led to a justice crisis of this magnitude— one where low-income people are not receiving adequate or any legal help for 93% of their civil legal problems. This project is intentionally positioned at the intersection of the criminal and civil legal systems in an effort to begin building bridges and collaboration between criminal and civil legal empowerment movements.

Beginning in early 2024, Innovation for Justice and the Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative partnered to understand the legal empowerment and civil legal problem-solving potential of jailhouse lawyers.

Research Methods and Questions

The project team intentionally used trauma-informed and participatory action research methods during this project. This included trauma-informed interview training for project team members facilitating interviews, feedback sessions throughout the process to ensure accurate understanding, co-researcher involvement through the design process, and co-creation of reports and deliverables. Through surveys and interviews with currently incarcerated and formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers, justice-impacted community members, and justice system actors, this project team identified and answered 11 research questions:

1. What civil legal issues do jailhouse lawyers assist community members with while incarcerated?

Jailhouse lawyers most commonly assist with family law and health law issues

2. How do jailhouse lawyers identify community needs?

Jailhouse lawyers identify community needs through trial and error and having discussions with those they are helping.

Jailhouse lawyers often take legal action through filing motions and initiating lawsuits once they identify a legal need.

When identifying community needs, jailhouse lawyers recognize how social issues, mental health, and legal issues often intersect.

3. What legal knowledge areas are jailhouse lawyers expert in and what gaps exist?

Jailhouse lawyers are experts in post conviction and prisoners’ rights issues, legal issues that arise in their own cases and lived experiences, and in conducting comprehensive research on any given legal issue.

Jailhouse lawyers have gaps in knowledge about civil legal issues outside of the prison context.

4. How are jailhouse lawyers acquiring civil legal knowledge now, and what pathways to amplifying their civil legal knowledge while incarcerated are possible?

Jailhouse lawyers’ civil legal knowledge can be amplified through increasing opportunities for knowledge building and sharing both during and after incarceration including connections with justice system actors.

Jailhouse lawyers predominantly acquire civil legal knowledge through helping other persons who are incarcerated with their legal cases and through sharing information with each other.

5. How and to whom do jailhouse lawyers pass on their legal knowledge?

Jailhouse lawyers predominantly pass on their legal knowledge to other incarcerated individuals through assisting them with their legal issues.

Jailhouse lawyers pass on their legal knowledge to other incarcerated individuals through institutionally authorized positions such as law class instructors, law library staff, and inmate counsel.

Jailhouse lawyers aspire to pass on their legal knowledge through legally empowering both the incarcerated community and their community when they go home.

6. What is the intersection of civil and criminal law and how do jailhouse lawyers navigate that intersection?

Civil and criminal law intersect at prisoners’ rights issues and post conviction relief, both of which jailhouse lawyers often litigate.

Jailhouse lawyers typically can distinguish between civil and criminal legal issues.

7. How are formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers using their legal knowledge and problem-solving expertise once they are home?

Formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers use their legal knowledge once home to pursue legal education and work within the legal profession.

Formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers also currently use their legal knowledge to advocate for and build towards a more effective and equitable justice system.

8. How do formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers want to use their legal knowledge and problem-solving expertise once they are home?

Once home, formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers want to engage in activism and advocacy centered around criminal justice reform and want to support incarcerated and justice-impacted communities through providing education and legal assistance.

If formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers were not restricted by IPL regulations and their status as convicted felons, they are keen to pursue more formal roles in the legal profession.

9. What relationships are important and helpful for jailhouse lawyers doing the work?

Jailhouse lawyers value relationships with mentors who can provide guidance and advice in their legal work and relationships with other jailhouse lawyers.

Jailhouse lawyers also welcome relationships with academic institutions and nonprofit organizations.

10. What perceptions and beliefs do the legal profession and the larger community hold about the capacity and abilities of jailhouse lawyers?

The legal profession and larger community perceive jailhouse lawyers as having a unique perspective that helps them empathize with clients and believe jailhouse lawyers could contribute more in the justice system if there were greater training and employment opportunities for them.

Legal professionals believe jailhouse lawyers contribute positively to the justice system and exhibit unique skills such as mentoring and attention to detail.

Some community members are receptive to assistance from a jailhouse lawyer.

11. What challenges and pain points do jailhouse lawyers experience in their legal work?

Jailhouse lawyers are cognizant of institutional resistance towards their legal work.

The institutional setting can negatively impact the mental wellness of jailhouse lawyers, especially through facing stigma, experiencing institutional hostility, and providing emotional support to others.

Jailhouse lawyers often struggle to build trust, which can impede their legal work.

Service Model Designs

Given what the research team learned through answering the identified research questions, the project team identified two potential service models that could benefit both currently and formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers in gaining legal knowledge, skills, and relationships to support them in continuing to do the important legal work. The project team shared these ideas and sought feedback from community members, currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers, formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers, and justice system actors.

Civil Law Modular Curriculum Certificate Idea (Civil Law 101 Course):

This intervention would offer a modular curriculum in civil law basics for jailhouse lawyers, particularly the substantive civil legal areas where justice-impacted communities have high rates of unmet civil legal need (e.g., housing instability, debt collection, family law, benefits, civil procedure, ethics for legal helpers, how to draft/respond to common civil legal documents). If offered to currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers, this intervention would NOT require regulatory reform, as incarcerated jailhouse lawyers can already provide civil legal help without UPL waiver. If offered to formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers, or jailhouse lawyers in reentry, more research is needed to understand whether there is a UPL reform component to this idea or whether jailhouse lawyers in community would engage with the curriculum in order to provide legal help in partnership with justice system actors in the community.

Connection Toolkit Idea:

This intervention is a jurisdiction-agnostic toolkit that supports jurisdictions in creating mentorship programs to support jailhouse lawyer learning and legal service to the community. The intervention trains jurisdictions on providing a variety of options for mentorship methods, such as session-based one-time sharing opportunities, structured mentorship programs, and systematic mentorship programs. There will be options for community/mentorship programs both between jailhouse lawyers and justice system actors and also just within the jailhouse lawyer community, allowing the user of the toolkit to have as much "customization" as they so choose.

Community Feedback

To learn more about what people thought about these ideas and their level of interest in their creation, we held 30 minute feedback sessions over zoom with 7 formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers and 3 justice system actors. We received survey responses from 99 community members and 147 currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers.

Based on feedback from co-researchers, it is evident that all system actors support continued work on both ideas. Currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers shared that they want access to anything that could support them in knowing and using the law, and they also want consistent interactions and relationships with potential connections. Formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers who participated in this project want to keep working in the legal realm and want connections that help with that.

Justice system actors who participated in this research are excited and welcome opportunities to collaborate and engage in reciprocal learning relationships with jailhouse lawyers. These justice system actors acknowledge the strength of empathy that comes from being in the same situation as those they are helping and also the heightened sense of accountability that exists between jailhouse lawyers and the incarcerated community members whom they serve. Lastly, community members are cautiously optimistic about receiving services from jailhouse lawyers. However, at this time, there are no plans or recommendations to pursue UPL reform efforts by this project team specifically related to jailhouse lawyers.

Given the feedback shared through the process reported in this paper, the project team recommends moving forward with the Civil Law Modular Curriculum idea because there are lower barriers to entry. Looking across all feedback, it is recommended that the course be in print or book format because electronic access is inconsistent across and within institutions. In order for this course to reach its intended audience, intentional care should be paid to whether it needs to be sent through regular mail communications or as legal mail, according to the rules and allowances in each participating jurisdiction and prison institution. Related to who should develop and host the curriculum, legal education institutions are well positioned to stay up to date on changes in the law and to provide as accurate information as possible while including the appropriate cautions in the print materials. Additionally, community members, formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers, and currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers identified legal education institutions as trusted course accreditors. While noting the status of legal education institutions as trusted accreditors, it is important to note that formal accreditation or certification is helpful but not necessary for the course to launch.

The project team recommends moving forward with the Connection Toolkit, but on a very small scale to better understand the challenges and barriers prior to expansion. The project team recommends starting at a single prison institution with a small cohort of currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers and connections so that the members can figure out what will work, what won’t work, what challenges are confirmed and what challenges arise that are unexpected. Through feedback, the project team learned that there will be some institutions that are more open to a connection toolkit than others. It might be beneficial to figure out what institutions have the lowest barriers to implementation first, and then show the benefit in a way that makes prison institutions excited before trying to scale.

Report and Additional Information

The full report includes more information about research methods, findings, and next steps.

Looking for more information about the work of jailhouse lawyers, directly from them?

Learn more about the Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative

Co-Researchers

Project Team Leaders

Cayley Balser, Principal Investigator, Director of Research, Innovation for Justice, University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law and University of Utah David Eccles School of Business

Stacy Rupprecht Jane, Co-Investigator, Director, Innovation for Justice, University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law and University of Utah David Eccles School of Business

Jhody Polk, Founder, the Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative

Tyler Walton, Deputy Director, Bernstein Institute, Managing Attorney, the Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative

Darren Breeden, Director of Community Engagement, the Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative

Project Team Members

Grace G. Capri K. Samantha B. Aouli R. Arin P. Collin C. Emily D. Paige M. Tyler F. Vivian S.

Formerly Incarcerated Co-Researchers

Rodney D. John V. Devon S. Stanley H. Jimmy S. Bruce R. Andy W.

Currently Incarcerated Co-Researchers

Clifford P. Remecos B. Craig H. Jamie Z. Lawrence A. Gary L. Surge S. Matthew G.T. Joseph S. Randy B. Armando R Alvaro L.H. Iron T. David F. Joseph D. Scott Z. Jeffrey W. Ignacio C. James J. Charles G. Derrick H. Marcellus F. Brian F. Jim H. Brian B. Anthony B. Jordan V.L. Ronald A. Nathaniel A. Chantell G. Anant K.T. Jose C. Erika E. Marvin B. Keith L.B. Shawn B. Antrell T. Domingo M. Jimmie E. Kelley D. Debbie N. Frederick M. Sam J. Troy W. Kentrell W. Ashton P. Paul T. David B. Omar J. Richard S. Sumpter P. Charles M. Michael B. Alann V. Robert B. Cobey L. Evlie P. Damon W. Cornelius R. Levy D. Monsour O. Milton L. Jocelyn N. William G. Randall M. Latthen D. Timothy O. Joey C. David B. Richard C. Kevin H. Derrick B. Michael K. Jared R. Joseph A. Henry M. Stephen A. Stephen B. Aaron C. Marques H. Samuel B. D. L. Danny W. Larry W. Danny T. William S. Dony A. David A. Steven S. Marcus S. Joseph D. Laura P. Christopher R. Armando H. Anthony C. Paul H. Daniel R. Robert M. Gregorio G. John B. Christian M. Jacob L. Roman J. Johnny W. Van B. Ricky S. Shayde M. Kareem W. Shaka S. John R. Tony E. Sky T. Amy M. Tyrone P. Sean S. Irving M. Roderick H. Derrick L. Richard M. Jason M. Ogunwole O. Charles T. Wayne V. John R. Charlie C. Antoine R. J.E. W. Lester A. Randy M. Clifton H. Gee G. Dwight B. Jerry C. Maurice H. Justin P. Major H. William M. Noel T. Shawn G. James B. Sharee M. Anthony A. Geoffrey R. Christopher F. James M. Dolen G. Benjamin T. Treenace B. Kenneth H. Larry M. Robert H. Sara K. Alan D. David Z. Emilio C. Cody A. Ontario R. Jachin W. Graham R. Jessica F. Karen M. Shavonne D. Hannibal E. Darrold A. Christopher C. Joseph C. Lawrence D. Corderral S. Jimmy H. Freeman A. Uhuru R. Alonzo J. Anthony M. Antoine R. D. M. Darius F. Eric E. Francisco R. Jamie H. John B. Jonathan E. Kevin S. Khalid D. Marcus B. Nedrick H. Nicholas D. Preston W. Richard S. Ruben B. Tommy M. Daniel G. Darren H. Stanley C. Jeffrey I.T. Maurice J. Jesse R. Paul C. Scott S. Lawrence D. Abbas A. John G.